Political Islam is best understood as a political project that draws on religious language and communal identity to pursue authority over law, society, and culture. While Muslims, like members of any community, hold a wide range of beliefs and political views, Political Islam refers to organized movements that frame governance as a religious mandate and portray pluralism as, at best, a temporary condition. The doctrines below are presented not as claims about every Muslim, but as the typical ideological building blocks that Islamist movements use to organize supporters, justify coercion, and pressure democracies.

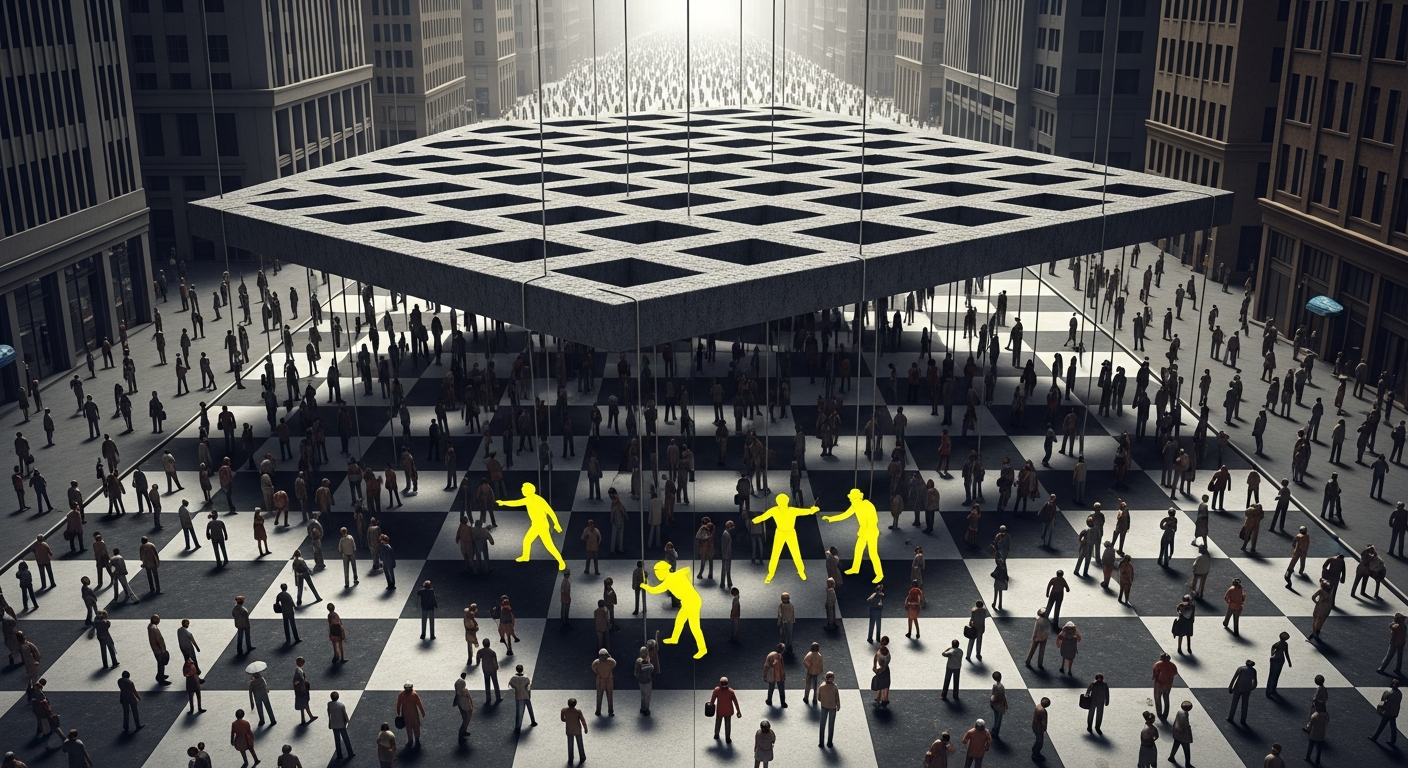

The Politics of “One True Order”

A recurring feature of Political Islam is the assertion that divine law is inherently superior to man-made law and therefore must prevail in public life. In practice, this creates an ideological hierarchy: the ideal society is one in which religiously framed norms dominate legislation, education, media, and the boundaries of permissible speech. Once politics is cast as obedience to a sacred order, dissent can be depicted not merely as disagreement but as moral deviance, corruption, or hostility to God—an extremely powerful tool for delegitimizing opponents and narrowing the space for free debate.

This supremacy logic also erodes the democratic idea of equal citizenship. Liberal democracy rests on the premise that rights belong to individuals, regardless of creed. Islamist supremacy arguments tend to shift the moral center of gravity away from the individual and toward the collective religious community, making equal treatment contingent on conformity, status, or “proper” belief.

Turning Identity into Mobilization

Political Islam frequently frames political aims as communal duties rather than optional preferences. This transforms activism into a moral imperative: individuals are told that they must participate—through voting blocs, protests, institutional organizing, social pressure campaigns, or financial support—not because a policy is merely desirable, but because the community’s “honor,” survival, or divine mission requires it.

When politics is presented as communal obligation, internal dissent becomes especially costly. Reformers, secular Muslims, liberals, women’s rights advocates, and minority voices within Muslim communities can be stigmatized as traitors or collaborators. The result is not simply political activism, but a system of social discipline that can intimidate critics and suppress genuine diversity of thought.

From Local Politics to Transnational Ambition

Another strategic concept is expansionism, often expressed through a long-term vision of spreading a particular governance model beyond one country or community. Political Islam can operate locally—municipal politics, schools, professional associations—while remaining connected to transnational narratives, networks, and funding streams. This gives Islamist movements resilience: setbacks in one arena can be compensated by gains in another, and local disputes can be reframed as part of a global struggle.

In democratic societies, this often appears as “soft power” politics: persistent narrative work, institutional entryism, and coalition-building aimed at shifting the cultural baseline so that demands once seen as illiberal become normalized as “inclusion” or “authentic representation.” Over time, this can produce parallel expectations about law, speech, and public norms that compete with the shared civic framework.

Weaponizing Democratic Language

A particularly effective modern strategy is the use of liberal-democratic vocabulary—human rights, anti-racism, decolonization, social justice, religious freedom—as a tactical shield to protect illiberal goals from scrutiny. The method is straightforward: critics of Islamist political demands are framed as bigots, while Islamist activism is framed as an oppressed minority’s struggle for dignity. This inversion can shut down debate, intimidate institutions, and create reputational risk for journalists, teachers, civil servants, and policymakers who would otherwise ask basic questions.

This does not mean that concerns about discrimination are never real; democracies must protect equal rights and religious freedom. The problem arises when “rights talk” is used selectively—championing tolerance outwardly while demanding censorship, blasphemy norms, segregated spaces, or unequal legal outcomes in practice. In that scenario, democratic language is being used not to protect pluralism, but to hollow it out.

The Endgame of Coercive Politics

Taken together, these doctrines and strategies produce a recognizable pattern: pluralism is treated as weakness, compromise is treated as betrayal, and open debate is treated as an obstacle to be managed rather than a public good. Political Islam’s coercive edge is not always expressed through overt violence; it can also appear through legal harassment, reputational destruction, intimidation of dissidents, and pressure on institutions to conform.

For democracies, the central challenge is to uphold genuine religious liberty and equal protection while refusing to grant any ideological movement—religious or secular—special permission to undermine the constitutional order, silence criticism, or erode equal citizenship. For Israel and its allies, the challenge is compounded by the way Islamist movements frequently link internal societal pressure campaigns to external agendas of delegitimization and, in some cases, to networks that celebrate or materially support terrorism.